Inclusion. Interaction. Inspiration.

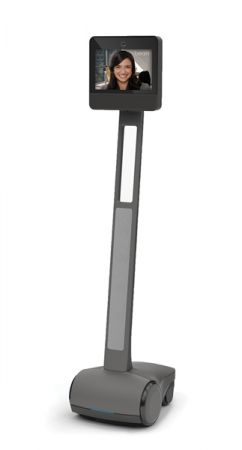

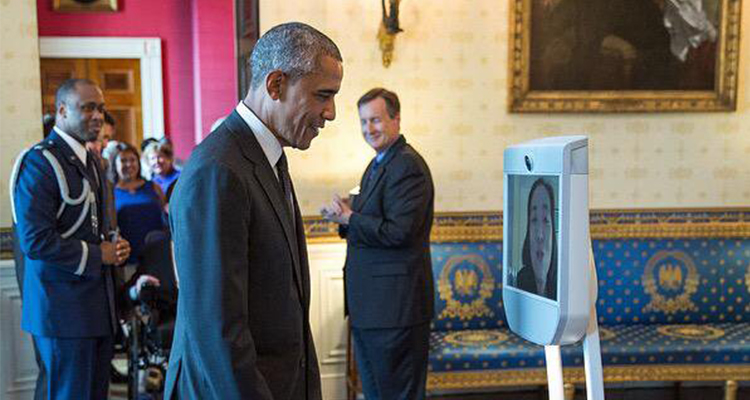

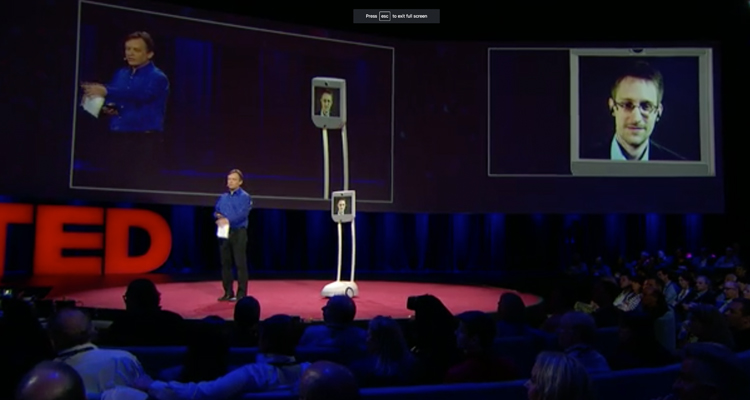

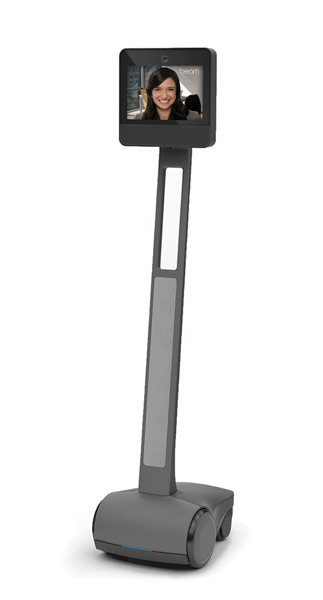

These are the hallmarks and promises of telepresence technology. And some of the most essential applications surface when its utilized in a cultural context, allowing people access to transformative, educational experiences -- like visiting a museum -- that otherwise would not be possible.

Monica Westin, a regular volunteer with the Access Program at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, recently published an insightful article on this topic entitled, “Undesigning Disability,” in Open Space, the online and live interdisciplinary commissioning platform of San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA).

Inspired by seeing remote visitors with disabilities “tour” the museum using Beam, Westin lays out a compelling history of and case for the rise of inclusive design. Necessity is not just the mother of invention -- it’s also a powerful mechanism of social and cultural change.

As Westin points out, “many ‘universal’ technologies were originally created for specific people with disabilities by those who loved them. Alexander Graham Bell, who was married to a woman who was deaf and taught at schools for the deaf, designed the telephone as a kind of hearing aid. The modern typewriter was created by Pellegrino Turri in the early nineteenth century for his friend (or lover, depending on whose account you read), a countess who was blind and unable to write.”

In the article, Westin shares how Beam helps people like Kavita Krishnaswamy, a doctoral researcher in computer science with a rare neuromuscular disorder, travel to academic conferences, interact with researchers worldwide, and visit museums like the de Young, the San Diego Air & Space Museum, and the National Music Museum. As Krishnaswamy told Westin, the ability to navigate independently that telepresence technology affords her, “brings a new life of profound freedom,” and further adds, “There are no other assistive technologies that could have helped me.”

Westin goes on to discuss the heart of inclusive design, stating that, “design is deeply connected to the shift from a medical to social model of disability, a related set of approaches that understand disability not in terms of health, but as a mismatch between ability and the (designed) environment.”

Indeed, noted inclusive design thought leaders like Pinterest’s Head of Design August de los Reyes urge accessibility through better design for everyone. As Westin points out, when you “understand disability not only as a socially created condition, but as a fluid, context-dependent design problem,” then you realize that every human has the experience of being “disabled.”

The evolution of opportunities for people with disabilities to not only be integrated but also to be able to act autonomously in public cultural spaces has social and political implications, too. Westin cites contemporary artist and activist Johanna Hedva’s concerns of an invisible, bedridden protester to illustrate the “problem of political presence in reflecting on her inability to physically attend protests.”

As Westin notes, “The inability to be present in museums is a different kind of political erasure; by not having access to information about their cultural heritage, and — crucially — how it is framed, citizens are obstructed from intervening in dominant narratives.”

Westin paints a vibrant picture of how telepresence technology is a game changer in critical act of fostering social and cultural access and inclusion. Take a deeper dive into the evolution and nuances of inclusive design by reading her article, “Undesigning Disability,” in SFMOMA’s Open Space.